The Importance of Social Connection in Infancy

Edited and Reviewed By Rose Perry, Ph.D. & Stephen Braren, Ph.D.

Social connections go far beyond buffering against loneliness, also serving as conduits of healthy development even in infancy. In the earliest weeks and months of life, supportive social connections set the stage for healthy social, emotional, and physical development.

Infants are often excluded from our definitions of social connectedness for one seemingly good reason: you can’t ask a baby if they feel lonely and expect to get an answer. Social connection is often defined as “the opposite of loneliness, a subjective evaluation of the extent to which one has meaningful, close, and constructive relationships with others.” Since the typical ways of measuring social connection don’t work for people younger than three, the issue of social connection in early life is often overlooked. But social connection is important for everyone regardless of age.

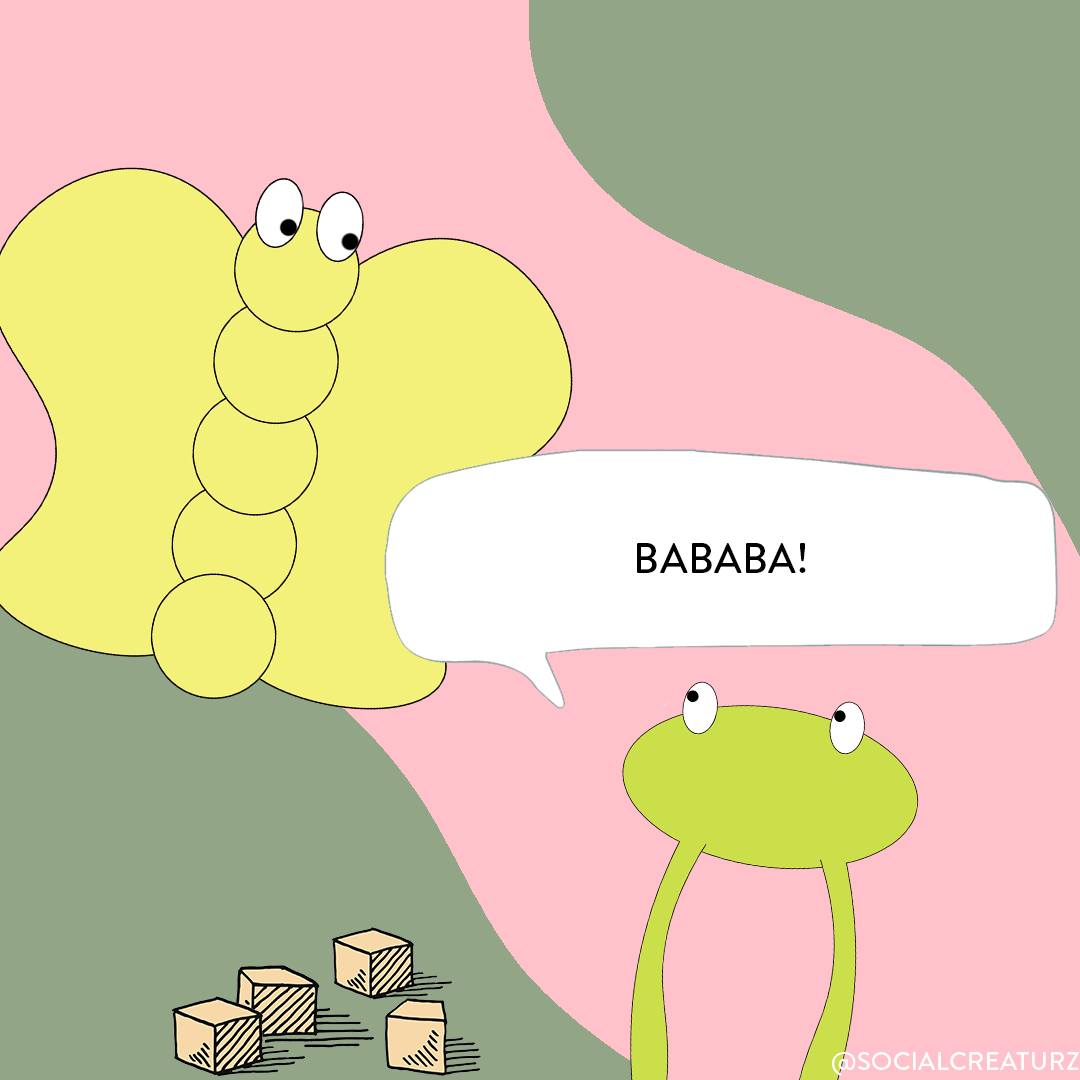

While social relationships are important across the lifespan, they are particularly important in infancy. This is because infants not only rely on connections with caregivers to survive, they also rely on early connections to lay the groundwork for more complex social connections that emerge in childhood and beyond. In fact, research shows that infancy is a “sensitive period” of development when the infant’s brain is particularly malleable to social experiences that can shape how the brain grows and develops [1]. In other words, social connection is important in infancy because it is foundational to short- and long-term health and wellbeing [2]. But how do babies form social connections?An infant’s need for social connections is typically met through bonding with their primary caregivers—the adults who attend to their needs, such as feeding and soothing, and interact with them daily. And in turn, healthy caregiver-child bonds fuel social development, preparing infants to forge social relationships with others as they grow.One way that caregivers create strong bonds with their infants is via serve-and-return interactions. During serve-and-return interactions, partners respond to each other in a timely manner with a relevant reply. For instance, caregivers can do this by responding to infants' babbles with relevant information, such as by naming the objects they are looking at [3]. Caregivers who are attentive and responsive to their infant’s bids for attention foster early word learning, conversational skills, and social-emotional wellbeing [3,4]. Serve-and-return social exchanges can and should happen in a fun way, especially during play. Play can be a joyful experience for both caregivers and infants. And, when play is socially interactive, joyful, and actively engaging, infants not only experience connection with their caregivers but also learn important skills like collaboration and confidence [5]. Play can be as simple as stacking blocks and saying, “look at you stack!” It can also be imaginative and creative, such as when a baby pretends to rock their doll back and forth and tell it a bedtime story, as though it were real. Play between caregivers and infants offers opportunities for rich social interactions and learning. Moreover, play is free, doesn’t rely on any special equipment or toys, and is accessible to everyone.While primary caregivers are key players in fostering social connections in infancy, babies are also active participants in making these connections.

Even though infants can’t yet speak, their early babbles, gestures, and play behaviors help them establish early social connections. Using their bodies, “words,” and objects within their reach, infants actively cue and participate in social interactions.Infants are astute observers of other people’s behaviors and body language. Well before babies can speak, they attend to cues in people's faces, voices, and bodies. And they create many cues of their own. Infants use eye gaze (where others are looking), facial expressions, hand gestures, and body movements to communicate with those around them. Even as early as six months, most infants begin to notice and follow gazes [6].Similar to gaze, gestures can also alert others to objects in the environment. Around 12 months, infants often look where others point and begin pointing themselves to request assistance or alert others to interesting things [6].When it comes to emotions, as early as four months, infants spend more time looking at their mothers’ happy facial expressions than sad ones, suggesting an early understanding of emotions. And infants act in line with the emotional cues they observe. For example, in lab studies, infants will approach difficult tasks when mothers display happy expressions but not fearful ones [7]. Over the second year of life, infants increasingly use social information when making decisions.Infants are also extremely in touch with the sounds in their environment, especially human speech. As young as two months, babies prefer listening to speech over nonspeech sounds and are particularly attentive to the sounds that appear in their native languages. Infants’ also communicate with their cries, grunts, and coos. Between five to eight months, infants begin babbling, making sounds like “bababa” [8]. Babbles resemble the rhythm and intonation patterns of their native languages. Infants actually understand many words and phrases before they can produce them. For example, when infants consistently look at an apple every time a caregiver says the word “apple,” even when there are other objects around, this is a good clue that they understand the word “apple.” During the second year of life, infants begin saying more words and combining words into short phrases such as “more cookie” or “want ball” [8]. Eventually, these early communications evolve into sentences resembling adult speech.Even very early in life infants have a range of social skills that enable social connection.

But what does the COVID-19 pandemic mean for infants who have limited interactions with others outside the home? Luckily, the latest research on technology use points to the benefits of live, video-mediated interactions [9]. Whereas organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics previously warned against any screen time for children younger than two, there are certain cases that are increasingly considered exempt from this suggestion. Studies of infants interacting virtually with their grandparents suggest that these interactions are beneficial for relationship building and conversational skills [9]. So long as virtual interactions contain serve-and-return exchanges, they can promote bonding and development. Although screen time shouldn’t replace face-to-face interactions, technology can be used intentionally as a tool to foster social connection.The importance of social connection goes far beyond preventing loneliness. Supportive social connections are conduits of healthy development at all stages of life—especially in infancy. Infants can’t necessarily speak for themselves, but when we tune ourselves in to them, their need and desire for social connection is unmistakable. Luckily, there are many effective (and fun) ways to support early social connections, regardless of circumstances. In-text references

[1] Gee, D. G., & Cohodes, E. M. (2021). Influences of Caregiving on Development: A Sensitive Period for Biological Embedding of Predictability and Safety Cues. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(5), 376–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214211015673

[2] Chambers, J. (2017). The neurobiology of attachment: from infancy to clinical outcomes. Psychodynamic psychiatry, 45(4), 542-563.

[3] Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Kuchirko, Y., & Tafuro, L. (2013). From action to interaction: Infant object exploration and mothers' contingent responsiveness. IEEE Transactions on Autonomous Mental Development, 5(3), 202-209

[4] Dunst, C. J., Gorman, E., & Hamby, D. W. (2010). Effects of adult verbal and vocal contingent responsiveness on increases in infant vocalizations. Center for Early Literacy Learning, 3(1), 1-11

[5] Konishi, H., Kanero, J., Freeman, M. R., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2014). Six principles of language development: Implications for second language learners. Developmental neuropsychology, 39(5), 404-420.

[6] Tomasello, M., Carpenter, M., Call, J., Behne, T., & Moll, H. (2005). Understanding and sharing intentions: The origins of cultural cognition. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28(5), 675–691. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X05000129

[7] Sorce, J. F., Emde, R. N., Campos, J. J., & Klinnert, M. D. (1985). Maternal emotional signaling: its effect on the visual cliff behavior of 1-year-olds. Developmental psychology, 21(1), 195.

[8] Cruz, S., Lifter, K., Barros, C., Vieira, R., & Sampaio, A. (2020). Neural and psychophysiological correlates of social communication development: Evidence from sensory processing, motor, cognitive, language and emotional behavioral milestones across infancy. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 0(0), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622965.2020.1768392

[9] Strouse, G. A., McClure, E., Myers, L. J., Zosh, J. M., Troseth, G. L., Blanchfield, O., ... & Barr, R. (2021). Zooming through development: Using video chat to support family connections. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies.